Above: Murray Matheson on a signed fan photo, Undated. Author’s Collection.

The 5 second version

The 5 second version

Born near Casterton in Victoria, Australia in 1912, Sidney Murray Matheson established himself on stage in the 1930s. He moved to the UK in 1937. His first British film was a small part as an Australian in the RAF, (which he really was) in The Way to the Stars in 1945. In the early 1950s he had moved to the US where he built an extraordinarily successful career playing character roles – often eccentric authority figures – in films and on TV. On his passing, obituaries noted the extraordinary breadth of his screen work, but also acknowledged his lifelong passion for the stage, which is less well known. He died in Los Angeles in 1985. (This article only lists some of his many screen and stage performances)

Growing Up in Australia

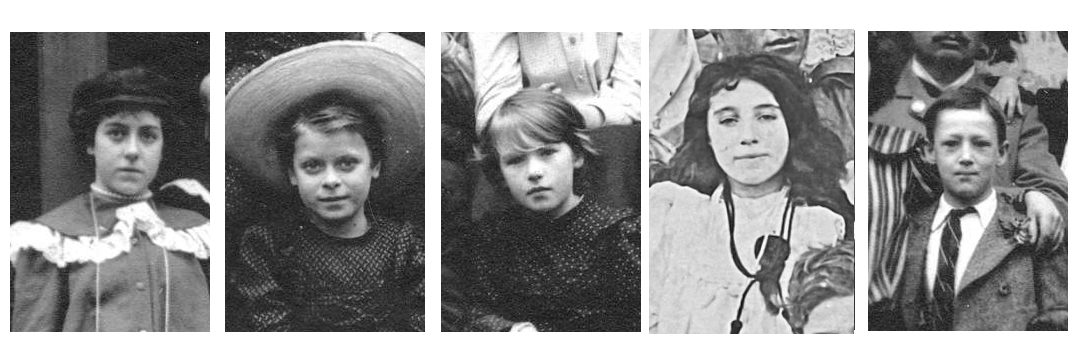

Sidney Murray Matheson was born at “Maryville,” a sheep station (ranch) at Sandford, near Casterton, Victoria, Australia on 1 July, 1912. He had four older sisters – Mavis, Joan, Roma and Beryl, and a brother who had died in infancy. While sheep grazing in Victoria’s “Western District” was very lucrative, it was not for the faint hearted. His parents, Kenneth Murray Matheson and Ethel Sunderland nee Barrett had both been born in country Victoria and were prepared to make the effort on the land. But when Murray was twelve his mother Ethel died – as a result of an awful mix of diabetes, rheumatic fever and heart failure. When Kenneth remarried in 1926, his new wife spent half an hour on the property before leaving for the city again, flatly refusing to live on the land. The second marriage did not survive.

Above: Murray’s older sister Mavis posing on a reaper and binder at Sandford in about 1915. In the 1990s, Museums Victoria collected a large archive of photos from rural Victoria, including this one and several others from the Sandford area. Via Museums Victoria Collections

Years later, Murray said one of his earliest memories was droving (herding) sheep – riding along behind his father. “I can still see him, his back completely black, covered with flies, the scourge of Australia” (Ogden Standard 16 June 1973). For part of his schooling Murray attended Geelong Grammar, a famous Australian independent boarding school, long favoured by wealthy Western District pastoral families and modelled on the English boarding school model, that is well known for educating Charles, Prince of Wales, in 1966.

On the stage

Murray had no intention of following tradition and staying on the land, much to his father’s disappointment. By 1934 he was living in leafy East Melbourne, whilst working as a bank clerk. In later years he recounted that his inspiration for becoming an actor was seeing the musical Sally. Probably starting off as an amateur, in the early 1930s he began to be associated with the Melbourne Little Theatre, where British actress Ada Reeve gave tuition in “Musical Comedy, Drama, Monologue, Film and Broadcasting”. He always claimed to have appeared in the musical Roberta with Cyril Ritchard and Madge Elliott in early 1935, perhaps in the chorus of this JC Williamson production. By early 1936, he was definitely a professional, on the road performing at small country towns through rural New South Wales and Queensland with George Sorlie‘s “tent company” (that is, they put up a tent for performances at each stop). Sorlie rather grandly called this the “English Comedy Company” and advertised his tour with the slogan “always a good show at Sorlie’s,” but it was really all designed to coincide with country agricultural shows. Their repertoire included While Parent’s Sleep, Wandering Wives and Ten Minute Alibi, and amongst the performers was a young Peter Finch, who in time became a good friend. For years, Murray’s experiences on this tour became the subject of endless witty stories about performing in remote Australia. Newspapers also reported Murray was engaged to the company ingénue, Leslie Crane. In June 1936, he took a leading role in a season of the musical Billie at Melbourne’s Apollo Theatre. Almost certainly encouraged to try his luck in London by actor friends like Cyril Ritchard and Madge Elliott, Murray boarded the SS Orsova for England in August.

Above: A youthful Murray Matheson, looking very like his friend Cyril Ritchard, who became a friend in the mid 1930s. The Telegraph (Brisbane) 11 Jul 1936 P12 Via the National Library of Australia’s Trove.

Not long after arriving, Murray found work with the Bournemouth Repertory Theatre company. In 1937 he was reported by a reviewer as demonstrating “adaptability and poise” in plays like If Four Walls Told and London Wall. (Bournemouth Graphic 19 Feb 1937). A year later he was performing with Edward Stirling’s English Players Company on an extended European tour, taking him to Paris, Vienna, Berlin and Warsaw, whilst performing Inferno and The End of the Beginning. He was “a find,” reported The Birmingham Mail (23 Oct 1940). However, with the outbreak of war he joined up, as did so many other young Australians living in Britain. By 1941 he was in the Royal Air Force (RAF). Leslie Crane, who had followed him to England in 1938 also left her repertory theatre company and joined the Women’s Land Army. But the couple did not marry. Years later, he claimed he had been briefly married, but did not say to whom or when (Sydney Morning Herald, 4 Feb 1968). He said he “did not like it.”

By 1939 Murray had been joined in London by his sister Roma, a restaurateur, and together they lived in Old Church St, Chelsea.

Above: Murray Matheson in his Royal Air Force uniform, c1941. Source; Cyril Ritchard album of theatrical performance and personal photographs, 1939-1944. Via National Library of Australia’s Trove.

The RAF and Murray’s early films

Many sources list Murray as a RAF Intelligence Officer, a title which might suggest many things – but what exactly, is today unclear. He was acting again by late 1944, or at least for some of the time. His early films date from this time – set in the RAF and written by Terence Rattigan. The first was a small supporting role in Anthony Asquith‘s The Way to the Stars – which featured John Mills and Michael Redgrave. Unfortunately the print currently in circulation appears to have been cut down for US release (under the title Johnny in the Clouds), and his role as Lawson, an Australian officer in the RAF, has all but disappeared – which is a pity, as contemporary reviews singled it out. Not so his role as Pete, the Australian radio operator in Journey Together, a tale of bomber command, directed by John and Roy Boulting, featuring Richard Attenborough.

There were also more real-life adventures before he was demobilised. He was reportedly in Moscow on some unspecified Admiralty mission at the end of the war, during which he broke his leg skating, or skiing. But it cannot have been all that bad an injury, as within a few months he was onstage at London’s Garrick Theatre in Better Late, with Beatrice Lillie.

Above: Screen grab of supporting players Hamish McNichol as Angus and Murray Matheson as Pete (the Lancaster bomber’s radio operator) in the final scene of Journey Together. The bomber’s crew are on a raft and have just been seen by a rescue aircraft because of the efforts of their excellent navigator (Richard Attenborough). Author’s collection. Following this he had a very small part in another war drama – Peter Ustinov’s Secret Flight, a story of the development of radar.

In 1948, the British Ministry of Information made a 25 minute docu-drama about the work of Dr George M’Gonigle, Chief Medical Officer in the 1920s and 30s for the northern English town of Stockton-on-Tees. Murray Matheson was cast to play M’Gonigle – one newspaper claimed he “was chosen for his sympathetic face and because, like Dr. M’Gonigle he has limp.” (Daily Herald, 10 Nov 1948, 3). McGonigle is hardly remembered in the 21st century, but he should be. A social pioneer – his reports on poverty and malnutrition impacted British social planning for years. For Murray, this role gave him valuable and lasting exposure as a capable performer, able to carry a successful film in a leading role.

Above: Screengrab of Murray in the lead role in One Man’s Story, a docu-drama made by the British Ministry of Information in 1948. Now in the public domain, it can be viewed online.

Move to North America

Sometime in late 1948 he travelled to Canada to appear for Brian Doherty – in The Drunkard, or the Fallen Saved an old temperance play, presented as “a stylised revue” now with music and played for comic effect. Although it was not to everyone’s taste, it appears to have been a reasonable success, and the play toured much of Canada before wrapping up in Chicago in March 1949. Murray must have enjoyed it because he was back in Canada doing another revue – There Goes Yesterday later that year.

Above: John Pratt, Charmion King and Murray in There Goes Yesterday. The Province (Vancouver), 17 March 1950, P6, via Newspapers.com.

Following this, in 1950 Murray appeared on tour in the US with old friends Cyril Ritchard and Madge Elliot in the 17th century comedy The Relapse, or Virtue in Danger. The play had recently been directed by Anthony Quayle at London’s Phoenix Theatre, before being brought to Broadway by Ritchard.

By the early 1950s, the US and soon California had become his home. But Murray’s connection to Australia remained surprisingly strong. Although he never returned to Australia (he said more than once that he would), Murray remained an active correspondent with his two surviving sisters and the Australian journalists he knew, more so than many other expat Australians.

A snapshot of a prolific US career

Murray’s letters home from the UK and later North America documented what must have been an exciting time in his career. His early US work was notable as a mix of “legitimate” stage, televised theatre (a common device used by TV networks in the early 1950s when they did not have enough material) and film. The film roles were at first a mix of menacing or alternatively affable authority figures – consider – the Communist brainwasher in The Bamboo Prison (1953) and Major MacAllister in King of Khyber Rifles (1953). He can also be found playing police inspectors, doctors, and even vicar roles, including a convicted reverend in Paramount’s formulaic 1952 colonial drama, Botany Bay, directed by Australian John Farrow, but mostly featuring British players.

Above: Leading players of Botany Bay (1952), James Mason, Patricia Medina and behind the frightened Koala (which briefly appears in the film) is Murray Matheson. The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana) 3 Feb 1952, P23, Via Newspapers.com

Baby-boomers would recall Murray fondly as a guest in many popular TV series of the time. The very long list of appearances includes The Man from UNCLE (1965), Get Smart (1966), The Invaders (1967), McMillan and Wife (1973), McCloud (1970), Hawaii Five-0 (1973) and Battlestar Galactica (1978). On many occasions, he reappeared – in a different episode and as a different character. Not so his regular role as Felix Mulholland in Banacek (1972-4), a detective series with George Peppard as private investigator Thomas Banacek. Here Murray played an extremely well read bookseller – a fellow wit like Banacek, whose encyclopedic knowledge assists in solving cases. (The most comprehensive list of his TV appearances is in David Inman’s 2 volume survey of Performers’ TV credits, Vol 2.)

It was while working on Banacek that Murray told reporters he had appeared in all of Noel Coward’s stage productions, which, given his passion for the stage, may well be true. On his passing in 1985, it was claimed he had appeared on stage almost 500 times.

Above Left; Murray in Visit to a Small Planet, The Greenville News, 6 June 1962, P6. Centre; Murray with Jane Powell in Peter Pan, The Los Angeles Times, 19 Dec 1965, P93. Right, Murray with Pat Galloway in Lock Up Your Daughters, The Los Angeles Times, 2 Oct 1967, P47. Via Newspapers.com

It is beyond the scope of this article to document all of Murray’s many appearances on the US stage, but a glance at US newspapers shows an impressively wide variety of roles played across the country. Reviews of his stage work were consistently positive, explaining why he was in such demand. In the musical Damn Yankees in 1965 he sang and danced skilfully as the Devil, “with a dry diabolical charm.” (San Francisco Examiner 5 Aug 1965, 30). When he appeared in Peter Pan later that year and again in 1968 he was “downright humorous and sometimes awesome” in the dual roles of the children’s father and Captain Hook (Independent, Long Beach, 21 Dec 1965, 8). He carried the leading role in Sleuth at the Little Theatre in Greenville, South Carolina, in 1972 with great skill – “an excellent portrayal of the snobbish, selfish but somehow likeable author…” (The Greenville News, South Carolina, 2 Feb 1975, 30). The stage clearly remained a passion and probably his preference.

Of Murray the man, his contemporaries had universally good things to say. Canadian born actor Beatrice “Bea” Lillie was a great friend in London – they had appeared together in revues like Better Late at the Garrick Theatre in 1946. In Hollywood, he was a close friend of Agnes Moorehead, sometimes escorting her to social events – as well as appearing with her in one episode of Bewitched.

In 1978 Murray was interviewed for Trader Faulkner‘s upcoming biography of Peter Finch. Murray recalled his occasional catch-ups with old friend “Finchie”, during which they would reminisce about George Sorlie’s tent shows in outback Australia. He said they would “both become terribly common, and Peter, despite the fact he was English, would become absolutely Australian and talk in ‘Strine’.* He was often more Australian in his outlook than I ever was.”

Murray Matheson died on 25 April 1985, following a stroke. He was only 72 and had been working almost to the end. His final film was a small role in Steven Spielberg‘s The Twilight Zone (1983).

However, for this writer, a favourite was his role as the Captain of the Queen Mary in Assault on a Queen.(1967). As a teenager, this writer made a decision to always be as urbane and cordial as the dapper and tanned Murray Matheson – playing the ship’s Captain, with officer’s cap just slightly askew, in the best ex-service tradition. You can watch the relevant clip at Turner Classic Movies here.

Above: Murray Matheson at the height of his TV activity, with his tanned face and distinguished white hair. Photo taken in about 1975. The Greenville News (South Carolina) 27 Jan 1975, P26. Via Newspapers.com.

*Strine – meaning a broad Australian accent, usually also interspersed with plenty of local and incomprehensible slang.

Nick Murphy

September 2021

References

- Text

- Amalgamated Press (1942) Picture Show Annual 1942

- Lotta Dempsey (1976) No Life for a Lady. Musson Books

- Trader Faulkner (1979) Peter Finch, a biography. Taplinger Pub. Co.

- David Inman (2001) Performers’ Television Credits Vol 2, G-M. McFarland

- Brian McFarlane (2003) The Encyclopedia of British film. BFI – Methuen

- Alex Nissan (2017) Agnes Moorehead on Radio, Stage and Television McFarland.

- J.P. Wearing (Ed)(2014) The London Stage 1930-1939 : a calendar of productions, performers, and personnel. Rowman and Littlefield

- Films available online via the Internet Archive

- Australian National Dictionary of Biography

- I. M. Britain (1996) ‘Finch, Frederick George Peter (1916–1977)‘

- Peter Spearritt (1990) ‘Sorlie, George Brown (1885–1948)’

- John Rickard (1996) ‘Ritchard, Cyril Joseph (1897–1977)’ & Elliott, Leah Madeleine (Madge) (1896–1955)

- State of Victoria: Births, Death and Marriages

- Sidney Murray Matheson, Birth certificate 1912. Doc 24110/1912

- Ethel Matheson, Death certificate, 1924. Doc 4749/1924

- Museums Victoria Collections

- Public Records Office, Victoria.

- Divorce Case Files, 1860-1940. VPRS 283. Kenneth Murray Matheson v Hannah Margaret Matheson, 1933/387

- National Library of Australia’s Trove

- The Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW) 15 Feb 1936, P6

- The Scone Advocate (NSW) 18 Feb 1936, P1

- The Warwick Daily News (Qld) 11 Mar 1936, P2

- Telegraph (Qld) 11 July 1936, P12

- The Herald (Melb) 8 Aug 1936, P21

- Table Talk (Melb) 8 Oct 1936, P18

- Telegraph (Qld) 27 March 1937, P14

- Telegraph (Qld) 12 June 1937, P14

- The Herald (Melb) 7 May 1940, P15

- The Home (Aust) Vol 22, No 1, 1 Jan 1941, P18

- The Herald (Melb) 10 Mar 1949, P19

- British Library Newspaper Archive

- Bournemouth Graphic 29 Jan 1937, P10

- Bournemouth Graphic 19 Feb 1937, P12

- The Stage 16 June 1938, P9

- Blyth News 12 Nov 1945 P3

- The Sketch, 15 May 1946

- Daily Herald, 10 November 1948 P3

- Newspapers.com

- The Age (Melb) 8 June 1934, P10

- The Province (Vancouver) 17 March, 1950 P6

- The Times (Louisiana) 3 Feb 1952, P23

- The Greenville News (South Carolina) 6 June 1962, P6

- The San Francisco Examiner, 5 Aug 1965 P30

- The Los Angeles Times 19 Dec 1965, P93

- The Los Angeles Times 2 Oct 1967, P47

- The Sydney Morning Herald (Syd) 4 Feb 1968, P40

- The Ogden Standard-Examiner (Utah) 16 June 1973, P23

- The Greenville Times (South Carolina) 27 Jan 1975, P26

- The Los Angeles Times, 26 April 1985, P30

This site has been selected for archiving and preservation in the National Library of Australia’s Pandora archive

Lotus Thompson from Queensland was briefly a silent star of some standing in Australia and the US, but her career was all but over by 1930. She appeared in some uncredited extra parts in the 1930s. Her few words as an extra here – “Please talk about them” seem to have an noticeable Australian twang.

Lotus Thompson from Queensland was briefly a silent star of some standing in Australia and the US, but her career was all but over by 1930. She appeared in some uncredited extra parts in the 1930s. Her few words as an extra here – “Please talk about them” seem to have an noticeable Australian twang.