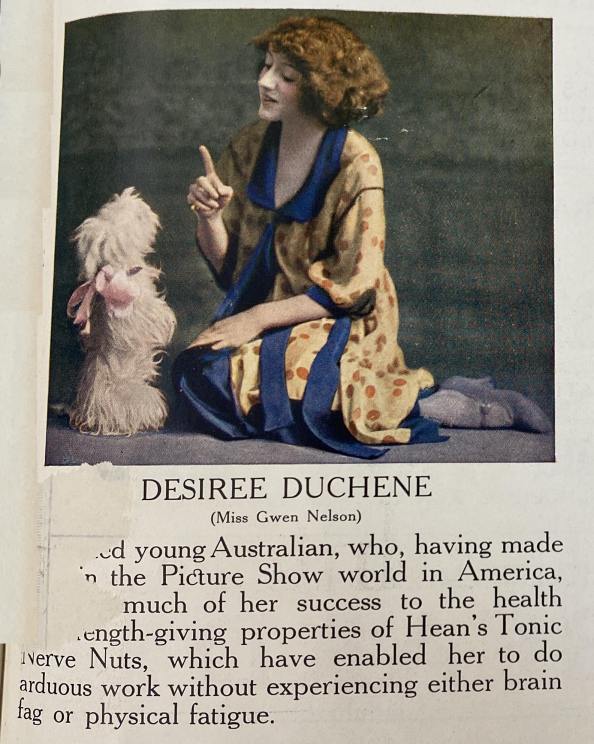

Gwen Nelson from Sydney, styling herself as Desiree Duchene on the cover of The Theatre Magazine in January 1922. [1]The Theatre Magazine (Syd) in January 1922. Via State Library of Victoria

The 5 second version

In his 1965 book, screen and stage historian Hal Porter listed Gwen Nelson as one of the early group of Australians in Hollywood – a list which included Enid Bennett and Mona Barrie – who reached “film stardom,” although he did not expand on her success or name any of her films.[2]Hal Porter (1965) P169 In truth, the evidence is overwhelming that Gwen Nelson was active, but not particularly successful.

For many actors, the experience of “trying your luck” in the US film industry in the early twentieth century ended up being unremarkable, and often, very disappointing. Talent and looks play a part in any actor’s success, but often luck played a part too. This was obviously the experience for 22 year old Sydney-born Gwendolyn Nelson, despite ambition that “seethed in [her] heart like a flood.”[3]See her mother’s poem below Gwen went to the US in 1917 and again in 1919, but despite the advantages of positive press in Australia, her family’s significant social capital and their numerous theatrical connections; for a decade she found only uncredited roles on the US stage and screen. In the end, she was also one of a number of Australian actors who met a miserable death from tuberculosis, far from home. Gwen Nelson died in San Francisco in early 1930, aged only 35.

Gwen’s Family

Gwendolyn Bourke, later Nelson, was born in Sydney in January 1895 to Patrick Bourke and Constance nee Shaw.[5]A birth certificate has yet to be identified, but the event was celebrated in The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 Jan 1895, P1 via National Library of Australia’s Trove Unfortunately lawyer Patrick Bourke proved to be a poor father. His drinking, intemperate behaviour and the resulting domestic violence he inflicted on Constance led to a divorce in 1899.[6]See Evening News, (Syd) 1 Sept 1899, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove and NSW State Archives, Divorce papers Constance Madeline Bourke – Patrick Benedict Bourke Happily for the little family though, Sydney accountant Herbert Nelson proposed and married Constance the following year. Sharing Constance’s interests in performance, he seems to have embraced Gwen as his own daughter and celebrated her successes as a good parent should. Living very comfortably in Sydney’s Elizabeth Bay, the family were associated with numerous fundraising and charity causes, and were well connected members of the Sydney social set. In the early 1910s, Gwen also appears to have attended actor Walter Bentley’s school of elocution and dramatic art, and was a contemporary or perhaps even a friend of Vera Pearce.[7]The Sun (Syd) 13 Aug 1913, P6 National Library of Australia’s Trove

If there was a hero in Gwen Nelson’s story, it must be her mother Constance, who supported her daughter through numerous challenges and was with her at the end. Born Constance Shaw in New South Wales in 1874, she was a voice and elocution teacher. In 1928, a US newspaper reported that Constance was on her 17th visit across the Pacific to San Francisco, to see her daughter Gwen.[9]This is almost certainly an exaggeration, although she did travel from Australia to the US numerous times. The San Francisco Examiner, 20 Apr 1928, P25 via Newspapers.com

In 1919, Constance told Sydney’s Theatre Magazine that at a lunch while visiting California, she had convinced hostess Mary Pickford to call her home “Dreamholme.”[10]The Theatre Magazine, 1 Nov 1919, P34, via State Library of Victoria However like so much of Gwen Nelson’s story, this claim is impossible to reconcile with the known historical record.

In the early 1910s, newspaper society pages listed young Gwen’s stylish appearances at patriotic concerts, balls and other good works around Sydney. After the outbreak of war in 1914, she danced and sang to raise funds for the Red Cross. When the first wounded men arrived home from fighting at Gallipoli, the Nelsons were on hand to help provide a concert.[12]Sunday Times (Syd)17 Oct 1915, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove There was a (short lived) engagement announced in February 1914.[13]The Sun (Syd)1 Feb 1914 P19 via National Library of Australia’s Trove

There is no evidence that Gwen found much work on the professional stage in Australia, although her impending departure to take up “moving picture work” in the US was announced with some fanfare in early 1917, seemingly with great confidence.[14]see for example Sunday Times (Syd) 28 Jan 1917, P25 and The Globe and Sunday Times War Pictorial (Syd)19 Mar 1917, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove This lack of Australian professional experience contrasts with the stage (and occasional screen) experience of many of her contemporaries who travelled to the US at about the same time – Enid Bennett, Louise Lovely, Dorothy Cumming and Judith Anderson.

Off to the US in 1917

Gwen arrived in San Francisco on April 9, 1917. She was a “professional actress” according to her landing card. The manifest for SS Sierra reveals she was to stay with Australian actor-director Arthur Shirley and his wife. Shirley had been working in Hollywood for several years, and had already appeared in credited roles in a number of films. Unfortunately, young Gwen Nelson appears to have experienced much less success than Arthur Shirley, and what little we know of her activity was via reports in Australian newspapers, illustrated by one or two grainy photos. There were, it seems, a few minor roles in 1917 – probably as an extra, in films for Fox and Triangle. Only one film outing by Gwen is known by title – For Liberty (1917), where she had a small uncredited role as the maid, playing opposite leading actor Gladys Brockwell. We know this because the film was screened especially for her parents and friends in Sydney, several years later. [16]Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners Advocate (NSW) 8 Aug 1919, P7, via National Library of Australia’s Trove

She also reputedly doubled for Theda Bara in the Fox film Salome (1918),[17]The Theatre Magazine (Syd) December 1919, via State Library of Victoria in the film’s dances.[18]This is a lost film and therefore it is impossible to verify the claim. A few minutes of the film survives here.

In November 1917, Melbourne’s Punch magazine was able to report that Gwen now drove her own car, and “as there is no reckless driving allowed in Los Angeles, she is not afraid of the traffic.”[19]Yes, they really wrote that. It is impossible to tell now whether it was a dry Australian joke or meant literally. See Punch (Melb) 15 Nov 1917, P41 via National Library of Australia’s Trove She was feeling so confident that she said she would motor through San Francisco to meet her mother, who was planning to arrive in the US in January 1918.

Notably, it was while Gwen was in the US in 1917, that the following poem by Constance Nelson appeared in syndicated Australian newspapers. The obvious anxiety expressed here by Constance explains the many voyages she took across the Pacific, but must also be typical of how many parents of hopeful starlets felt.

MY GWEN.

I’m sitting alone in the twilight,

At the end of a long, long day.

I am dreaming of you, my Gwen dear,

Who is ever so far away.

I see your eyes like sapphires,

Intermingled with rare pearl;

I fancy I see your smile, dear;

I can almost feel a curl.

I know ’twas ambition that sent you

It seethed in your heart like a flood;

But, ah, my Gwen, how I miss you

It sure is the call of the blood.

I am sitting alone in the twilight,

And to God I offer a prayer,

That He will watch o’er my Gwen dear,

And Keep her in His care.

CONSTANCE NELSON. [21]There was no further comment accompanying the poem, and it could conceivably be people with the same names, at the same time. The Muswellbrook Chronicle (NSW) 23 June 1917, P6 via National Library of … Continue reading

Gwen returned to Australia, with Constance, in April 1918. There were, again, vague accounts of what she had done in the US. For example, The Bulletin magazine reported “For over a year Gwen Nelson climbed ladders, dived into space, crossed into Mexico, and had a revolution for breakfast, all for Fox Films. Now she’s resting… with Mum and Dad.”[23]The Bulletin (Syd) 30 May 1918, P18 via National Library of Australia’s Trove

During 1918, she was again often mentioned in society news from Sydney. Being wartime there were more patriotic balls, and finally, Victory balls, and when US actress Fayette Perry toured Australia in 1917-1918, Gwen and her parents entertained. In December 1918, Gwen danced in a short run of the Australian musical revue The Girl from USA.[24]The Daily Telegraph (Syd) 3 Dec 1918, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove

The 18 months spent at home was never publicly explained or contextualised. But in advertising, Heans Pty Ltd began to profile her as a user of their products and in a 1924 advertisement, claimed their “Nerve Nuts” had cured her after a nervous breakdown. Perhaps the time spent back in Australia really was needed for a recovery from the struggles she had faced in the US film industry.

A second try in the US – 1919

In August 1919, Gwen boarded the SS Ventura, bound for San Francisco again. Her destination this time was New York, while Australian papers assured readers that she had a contract with Fox Films, and it was at this time she briefly used the stage name Desiree Duchene.[26]Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 8 Aug 1919, P7 via National Library of Australia’s Trove She confidently gave her profession as “Movie Actress” on her US landing card. Constance travelled to the US to visit her again in July 1920.

Of her stage and picture work, we again have only patchy information and there is nothing to be found credited to the new stage name. There were reports back in Australia about “film work” being done, but very little detail. In 1921 The Bulletin listed Gwen as having minor roles in Heliotrope (1920) and Why Girls Leaves Home (1921) but these films do not survive.[27]The Bulletin Vol. 42 No. 2152,12 May 1921, P50 via National Library of Australia’s Trove A lengthy interview conducted with Gwen in 1924 for Truth seemed to infer she worked with or studied with Florenz Ziegfeld’s choreographer Ned Wayburn in New York and perhaps even appeared in some of the Ziegfeld Follies.[28]Table Talk (Melb) 29 Nov 1923, P10 via National Library of Australia’s Trove The best documented claim indicates she subbed for Gloria Swanson in the dance scenes for the film Zaza (1923).[29]Truth (Syd) 13 Jan 1924, P16 via National Library of Australia’s Trove This film survives, but picking Gwen out with confidence is extremely difficult, and like most stand-ins she was not listed in the film’s credits.

It seems all of these film roles were cameos – and none of them were credited. Her stage appearances are even harder to find, but from the little we know is seems she was a speciality dancer in ensembles and again, usually not credited. She returned to Australia again in November 1923, and provided some more commentary on working in the US. In one newspaper interview she explained that she had found the screen too exacting, and that she much preferred the stage, the lights and the audience reactions.[31]Sunday Times (Syd) 23 Nov 1923 P3 via National Library of Australia’s Trove

In May 1924, Gwen was back in the US once more. She was dancing by August,[33]The Sacramento Bee (Cal) Aug 2, 1924, P26 via newspapers.com while her newly arrived mother mixed with Hollywood’s expat Australians, like Snowy Baker and Enid Bennett.[34]Evening News (Syd)16 August 1924, P8 via National Library of Australia’s Trove Rather ominously however, once back in Australia again, her mother developed a keen interest in supporting TB (tuberculosis) charities. [35]Evening News (Syd) 31 Aug 1925, P12 via National Library of Australia’s Trove There were more visits by Constance to the US over the next few years, and finally in April 1928, reports that Gwen was seriously unwell.[36]The Bulletin, 25 April 1928, P46 via National Library of Australia’s Trove Unfortunately we do not know what performance work Gwen did in the later 1920s, although an engagement to William Loftus, a US lawyer, was cheerfully announced in early 1929.[37]The Bulletin, 16 Jan, 1929, P42, via National Library of Australia’s Trove

So if Gwen was not the raging success contemporary Australian publicity suggested, where did it all come from? The answer is that these stories of Gwen’s stage success and film stardom easily captured the mood of 1920s Australia. In her groundbreaking work on women in Australian cinema, Andrée Wright has written “at the time, [these film success] stories convinced readers that ‘with very few exceptions, every Australian who ha[d] ever gone to America ha[d] succeeded beyond expectations.’ “[39]Andree Wright (1986) Pps18-19. The inserted quote is from Picture Show, 2 August 1919. Perhaps that nationalist-tinged view also obscured another simple fact – Gwen was a Sydney society girl who had the resources to pursue her interests, but did not have the great talent that some suggested.[40]Admittedly, without reviews or any surviving films, this is conjecture

Gwen Nelson succumbed to tuberculosis on January 5, 1930. Her mother Constance was with her when she died. She was buried at Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery in San Francisco.

Despite the disappointing reality of her US experience, Gwen Nelson remained firmly in the minds of Australians for some time. Pharmacist G W Hean produced an array of medicines (Heenzo, Hean’s “Nerve Nuts”, Hean’s “headache wafers” etc) and often made use of home grown actors and celebrities to advertise these in the press. Amongst the well known actors were Gladys Moncrieff and Cyril Richard, and Australians less well-known working overseas – including Nina Speight and Gwen Nelson.[41]See Clay Djubal’s short history of G.W. HEAN PTY LTD at the Australian Variety Theatre Archive

References

Possible surviving films

Primary Sources

- National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa, Papers Past.

- National Library of Australia, Trove

- New South Wales State Archives

- State Library of Victoria

- Ancestry.com

- ProQuest Historical Newspapers

Text and Web

- Clay Djubal (2001) ‘That men may rise on stepping stones’: Walter Bentley and the Australasian stage, 1891‐1927, Journal of Australian Studies, 25:67, 152-161, DOI: 10.1080/14443050109387649

- Clay Djubal (2017) G.W. HEAN PTY LTD (a short history). Australian Variety Theatre Archive. (27 December 2017)

- Marilyn Dooley (2002) ‘Shirley, Arthur (1886–1967)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed online 11 August 2023.

- Eric Porter (1965) Stars of Australian Stage and Screen. Rigby Ltd.

- Andrée Wright (1986) Brilliant Careers, Women in Australian Cinema. Pan Australia

Nick Murphy

August 2023

Footnotes

| ↑1, ↑4 | The Theatre Magazine (Syd) in January 1922. Via State Library of Victoria |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Hal Porter (1965) P169 |

| ↑3 | See her mother’s poem below |

| ↑5 | A birth certificate has yet to be identified, but the event was celebrated in The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 Jan 1895, P1 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑6 | See Evening News, (Syd) 1 Sept 1899, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove and NSW State Archives, Divorce papers Constance Madeline Bourke – Patrick Benedict Bourke |

| ↑7 | The Sun (Syd) 13 Aug 1913, P6 National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑8, ↑10 | The Theatre Magazine, 1 Nov 1919, P34, via State Library of Victoria |

| ↑9 | This is almost certainly an exaggeration, although she did travel from Australia to the US numerous times. The San Francisco Examiner, 20 Apr 1928, P25 via Newspapers.com |

| ↑11 | The Mountaineer (Katoomba NSW) 20 Nov 1903, P3 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑12 | Sunday Times (Syd)17 Oct 1915, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑13 | The Sun (Syd)1 Feb 1914 P19 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑14 | see for example Sunday Times (Syd) 28 Jan 1917, P25 and The Globe and Sunday Times War Pictorial (Syd)19 Mar 1917, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑15 | The Triad, Jan 10, 1921, via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑16 | Newcastle Morning Herald & Miners Advocate (NSW) 8 Aug 1919, P7, via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑17 | The Theatre Magazine (Syd) December 1919, via State Library of Victoria |

| ↑18 | This is a lost film and therefore it is impossible to verify the claim. A few minutes of the film survives here. |

| ↑19 | Yes, they really wrote that. It is impossible to tell now whether it was a dry Australian joke or meant literally. See Punch (Melb) 15 Nov 1917, P41 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑20 | The Mirror (Syd) 29 Sept 1917, P9 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑21 | There was no further comment accompanying the poem, and it could conceivably be people with the same names, at the same time. The Muswellbrook Chronicle (NSW) 23 June 1917, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑22 | The Theatre Magazine (Syd) Dec 1919, P23, State Library of Victoria |

| ↑23 | The Bulletin (Syd) 30 May 1918, P18 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑24 | The Daily Telegraph (Syd) 3 Dec 1918, P6 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑25 | The Theatre Magazine (Syd) Dec 1, 1919, P 55, Via State Library of Victoria |

| ↑26 | Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate, 8 Aug 1919, P7 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑27 | The Bulletin Vol. 42 No. 2152,12 May 1921, P50 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑28 | Table Talk (Melb) 29 Nov 1923, P10 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑29 | Truth (Syd) 13 Jan 1924, P16 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑30 | The Theatre Magazine, 1 Nov 1923, P19. Via State Library of Victoria |

| ↑31 | Sunday Times (Syd) 23 Nov 1923 P3 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑32 | The Daily Telegraph (Syd) 11 Mar 1924, P12 via newspapers.com |

| ↑33 | The Sacramento Bee (Cal) Aug 2, 1924, P26 via newspapers.com |

| ↑34 | Evening News (Syd)16 August 1924, P8 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑35 | Evening News (Syd) 31 Aug 1925, P12 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑36 | The Bulletin, 25 April 1928, P46 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑37 | The Bulletin, 16 Jan, 1929, P42, via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑38 | The Home, 1 Aug 1928, P69, via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑39 | Andree Wright (1986) Pps18-19. The inserted quote is from Picture Show, 2 August 1919. |

| ↑40 | Admittedly, without reviews or any surviving films, this is conjecture |

| ↑41 | See Clay Djubal’s short history of G.W. HEAN PTY LTD at the Australian Variety Theatre Archive |

| ↑42 | The Herald (Melb) 10 December 1924, P5 via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

I still have 6 bottles of Heenzo at home and at this very moment using it. I’m 66 and all my life I have used Heenzo and no chemicals! I swear by Heenzo and are after more or do I have to get 1 off these analysed?

Might be a good idea to get it analysed – the product seems to have disappeared from shelves 60 years ago!