Henry Matsumoto, undated photo. Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: SP42/1, C1931/3848.

This article was originally published in On Stage, the online journal of Theatre Heritage Australia.

The Five second version.

‘Henry’ Kakusakuro Matsumoto, was born in Japan on 8 September 1879. He spent most of his adult life in Australia, and despite the fact he lived in a limbo-land of non-citizenship—a consequence of the racist White Australia policy—he appeared on stage in Australia in the 1910s, and in two Australian films made by Fred Niblo, followed by a stint on stage in the US. However, his footsteps through the historical record are faint. He was never interviewed and only rarely reviewed, and the Second World War swept away memories and cultural records of the Japanese in Australia. Fortunately, the National Archives of Australia hold very comprehensive files on ‘aliens’ who resided in Australia in the early twentieth century, and here we can meet Henry Matsumoto.[1]National Archives of Australia. SP42/1, C1931/3848, Henry Kakusaura Matsumoto

When South Australia’s Daily Herald announced in November 1912 that Henry Matsumoto was the “first Japanese to appear on the Australian stage”, they were, or course, engaging in a piece of journalistic shorthand.[3]Daily Herald (Adelaide) 27 November 1912, p9 He wasn’t. The success of touring Japanese acrobats in Australia in the late nineteenth century was well known at the time and has been recorded by Mark St Leon.[4]St Leon (2011) pps155-6 In spite of discriminatory colonial and later national legislation, since labelled as the White Australia policy, there were in fact, a few performers of Asian backgrounds who achieved a degree of success in Australia. Most famous perhaps was Melbourne-born Rose Quong (1878-1972), whose journey to the stage has been documented by Angela Woollacott. The story of others of mixed race, including the celebrated dancer of the late nineteenth century, Saharet (1878-1964), is now also well documented, despite her lifelong efforts to hide her origins of Chinese-Australian ancestry.

Moving to Australia

Kakusakuro Matsumoto[5]He apparently adopted the first name ‘Henry’ on arrival in Australia arrived in Queensland in November 1899. He was employed as a clerk at the Yamato Company Store in Townsville, one of the colony’s first silk suppliers.[6]Killoran (2023) p153 Born in Osaka, a Japanese Treaty Port, he had probably acquired a high degree of fluency with English language before arriving in Townsville, which had a sizeable Japanese population working in the sugar and pearling industries.[7]Sizeable in the north of Queensland, but Armstrong (1973) p8 estimates there were never more than 3,000 Japanese in the entire colony Townsville even boasted a Japanese Consulate office at the time. Queensland’s delay in introducing restrictive immigration laws—as other Australian colonies had done—apparently benefited Henry.[8]See Neville Meaney (2007) p18-19

In 1901, only a few years after Henry’s arrival, Australia’s new Commonwealth Parliament passed the Immigration Restriction Act. In Alfred Deakin’s(1856-1919) words, the law’s stated intention was “the prohibition of all alien coloured immigration, and… by reasonable and just means, the deportation or reduction of the number of aliens now in our midst.”[9]Attorney-General Alfred Deakin, 12 September 1901 The law’s mechanisms for excluding “alien coloured immigration” included the infamous dictation test, applied when non-Caucasians arrived to seek entry to Australia. Exemptions could be granted, but the intention was avowedly to create a ‘White Australia.’

Henry’s National Archives file shows that in 1904 he left Townsville to work as a valet for pastoralist Philip Gidley King at Goonoo Goonoo station near Tamworth, in New South Wales. Then for the three years 1905-7 he was a valet in Sydney, to Sir Frederick Darley, one time Chief Justice and Lieutenant Governor. In 1908 he served as a valet for E.H.L. von Arnheim, Deputy Master of the Sydney Mint. These were impressive appointments, which also provided him with useful character references—just the sort of references required to support exemptions from provisions of the 1901 Act.

In 1909 Henry moved on again, apparently to establish his own import business – to cater for the fashion in oriental fabrics and ceramics—a contradiction indeed in a country wishing to exclude non-Caucasians. Henry also married Ada Maud White, an English dressmaker, in Melbourne, in December 1909. A daughter was born of the union in 1912, and a son in 1913. But the marriage did not mean that Henry became British or Australian. Rather, it meant Ada became a Japanese national.

A New Opportunity beckons

In July 1912, US actors Fred Niblo(1874-1948) and Josephine Cohan(1876-1916) arrived in Australia to launch a tour of American farces for J.C. Williamson, the first being George M Cohan’s Get Rich Quick Wallingford. Niblo and Cohan would have been quite aware that in New York, a Japanese American named Yoshin Sakurai had successfully taken the supporting role of Yosi the Japanese valet in 1911.[10]See Esther Kim Lee (2006), p14. However, Elizabeth Craft suggests a Korean actor “Du Gle Kim” first played the role in the US. Craft (2024) p100 The character of Yosi had not appeared in the original Wallingford stories by George Randolph Chester—it had been added to the play by Cohan.[11]Elizabeth Craft (2024) p236

As Josephine Lee argues, the more authentic use of real Asian actors on stage instead of Caucasians in ‘yellowface’ did not change the fact they were “onstage for the benefit of white spectators, and their performances strongly framed by assumptions about their racial and cultural difference.” They were “exotic novelties” she concludes.[12]Josephine Lee (2015) p63

As Elizabeth Craft notes, the minor character of Yosi, valet to the con-man J Rufus Wallingford, both reinforced and undermined existing stereotypes. The character is mocked and dehumanised as ‘the Jap.’ However, when a resident of Battlesburg—the fictional town where the action of the play is set—assumes he is Chinese and makes an offensive comment, Yosi retorts in fluent English and appropriate US slang, “Go on, you big stiff.”[14]Elizabeth Craft (2024) p100

Melbourne Punch reported that Niblo had asked the Japanese consulate in Sydney for help in casting the part of Yosi and Henry Matsumoto had been nominated.[15]Punch (Melbourne) 21 Nov 1912, p42 The pragmatic Niblo obviously felt the previously unknown Henry could take the part. Table Talk noted Henry spoke “very fair English” and claimed he had previous stage experience in Japan. Henry’s skill with English was important, however, given the play was so dependent on distinctive US slang and mannerisms for comic effect.

During their three-year performance tour for J.C. Williamson, Niblo and Cohan presented eight comedies, all of which were a success.[16]The tour was extended three times; in December 1912, May 1913 and May 1914. The contracts survive in the Australian Performing Arts Collection In addition to Get Rich Quick Wallingford, Henry also appeared in speaking roles in Excuse Me! and Officer 666 although these were again minor roles—as a porter and valet.

The company toured all the Australian capitals and went to New Zealand twice. The travel to New Zealand meant the troupe left the country, and with their return, Henry was potentially exposed to the provisions of the Immigration Restriction Act—including the dictation test. But such was the influence of J C Williamson he was exempted at their request, and Henry breezed back into Australia with the rest of the cast.

In May 1915, Fred Niblo quickly directed film versions of Get Rich Quick Wallingford and Officer 666 for J.C. Williamson, using the stage cast. These were fairly unimaginative, static camera films. As Ralph Marsden has explained, J.C. Williamson turned to making films because they were concerned about the release of US-made films, based on plays to which Williamson’s already held the Australian stage rights. The Firm probably assumed that filmed plays might provide a means to safeguard their claim on the plays and provide income from distribution to less populous parts of the country.[17]Marsden (2009) p4

Existing credit lists show Officer 666 included Henry, and it is reasonable to conclude he also appeared in the (now lost) filmed version of Get Rich Quick Wallingford, made only a few weeks earlier.[18]Pike & Cooper (1980) p80 Writing in 2009, Ralph Marsden was obviously lucky enough to see all of the 40 minutes of Officer 666 that survives, but only a two minute clip is freely available to us today—and that clip does not include Henry. In the end, neither film proved successful at the Australian box office, and J.C. Williamson soon abandoned its filmmaking.

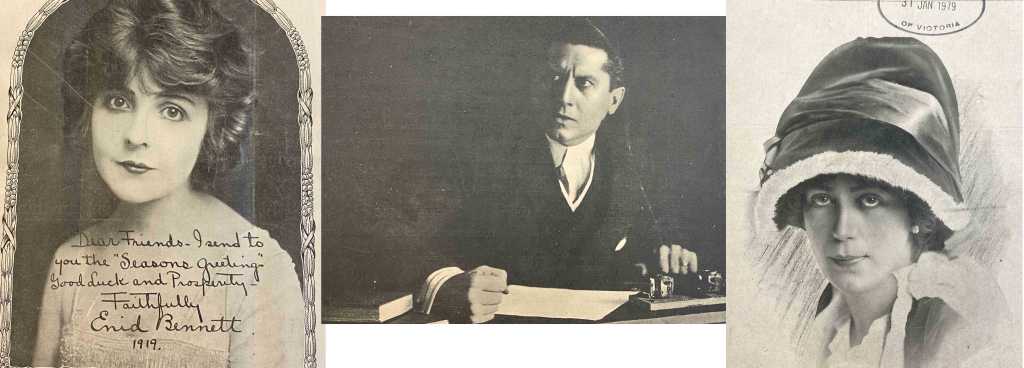

Niblo and Cohan finally wrapped up their tour in June 1915 and returned to New York, taking two promising young actors with them—Enid Bennett(1893-1969) and Pirie Bush(1889-1965). Did Henry Matsumoto also dream of an ongoing career on the stage? It would seem he did.

Image courtesy of the National Archives of Australia. NAA: SP42/1, C1931/384

In December 1915, Hugh Ward, the J.C. Williamson Manager who had previously contracted Fred Niblo and Josephine Cohan, returned to Australia with a new US acting partnership—Hale Hamilton and Myrtle Tannehill. Their repertoire again included the very popular Get Rich Quick Wallingford. Several Australians were on hand to reprise their supporting roles from the Fred Niblo-Josephine Cohan tour. But not Henry Matsomoto.

In October 1915, Sydney’s The Theatre Magazine reported that Henry had been cabled by Fred Niblo, urging him to come to New York for acting work.[19]The Theatre Magazine (Sydney) 1 October 1915, p16 He arrived in San Francisco on the SS Sierra in January 1916. On arrival in the US, Henry listed his profession as actor, and his contact in the US as Fred Niblo, care of George M Cohan, New York. For the very thorough US immigration records, Henry was also required to give his nationality. For this question he stated he was Australian, although this was not the case. As far as the Australian Government was concerned, he was Japanese—and there was no provision for dual citizenship at the time.

Back in Australia, the Hamilton-Tannehill performance of Get Rich Quick Wallingford failed to find another Japanese actor to take the role of Yosi. Instead, Frank Seegoolam was engaged. He was a former Officer’s cook from HMS Cambrian and later a personal cook for several wealthy Sydney families. Originally from Mauritius, then a British colony, Seegoolam was a British subject and thus his Australian residency could never be questioned.[20] National Archives of Australia. C1912/21405, Frank Seegoolam But in Get Rich Quick Wallingford the character of Yosi had to be changed to Hassan,[21]National Library of Australia. J.C. Williamson scrapbooks of music and theatre programmes, Sydney and Melbourne, 1905-1921. PROMPT Scrapbook 8 – Vol 3, p129 and presumably some of the dialogue was changed too.[22]The Daily Telegraph (Sydney) 2 September 1916, p2 The racial stereotype was simply transferred from one ethnic group to another.

Henry in the US 1916-1918

After his arrival in the US in January 1916, Henry disappears from the historical record in the US for about twelve months. He may have appeared on stage, but there is, so far, no record that he did. In later life he listed travelling salesman as one of his occupations, perhaps this is what he did in New York in 1916. However, in early 1917 Hale Hamilton and Myrtle Tannehill returned to New York and a revival of Get Rich Quick Wallingford was soon announced. In the cast was Henry Matsumoto, reprising his role as Yosi.

The revival had a short run at two theatres in New York and by the end of May it was over. So too, apparently, was Henry’s acting career. He had returned to Australia by August 1918, when, National Archives records indicate, he had recommenced his import business and added teaching Japanese to his resume.

Henry Matsumoto had long abandoned his dreams of acting by 1934, but he was still required to apply for exemptions and permission to re-enter on his return to Australia from business trips to China and Japan. On his final trip to Japan in 1934, he became seriously ill after stopping over in Shanghai. He suffered a cerebral haemorrhage and died on 27 September while at the Osaka Imperial University Hospital, Japan. In the best traditions of reporting about the exotic East, Australian newspapers speculated that the well-known Sydney merchant had been poisoned by some ‘obscure poison’ while on the ship. Sydney’s Truth newspaper ran the headline:

“Tragic fate of popular Sydney Japanese. Scientists baffled. Did orient love potion send him mad?”

It claimed he had been seduced, drugged and robbed by a beautiful Filipino girl who had joined the ship in Manila—a type of Mata Hari story.[23]Truth (Sydney) 14 October 1934, p21 The story dragged on for months. It remains completely unclear whether there was any truth to this story at all.

Despite his early death, the ongoing prejudice and the endless legalities Henry Matsumoto endured, he remains someone we should celebrate. A minor but determined actor and a successful businessman, he never showed any interest in making his life anywhere but Australia, even though the country would not accept him as a citizen.

Following his death, Henry’s family showed no interest in moving either. Ada went through the process of regaining her British citizenship, and seven years later, after war broke out in the Pacific, the family changed their surname to Maxwell.

Twenty years after Henry’s death, probate on his estate was finally granted to his two children.

Nick Murphy

November 2025

Sources

Collections

- Australian Performing Arts Collection, Arts Centre, Melbourne, Australia.

- National Archives of Australia.

Text

- J. Armstrong, ‘Aspects of Japanese Immigration to Queensland before 1900.’ Queensland Heritage, Vol 2, No 9, 1973. University of Queensland espace Library.

- Elizabeth T Craft, Yankee Doodle Dandy. George M. Cohan and the Broadway Stage, Oxford University Press, 2024.

- Tianna Killoran, The near north and the far north: The Nikkei community in North Queensland, 1885-1946. PhD Thesis, James Cook University, 2023.

- Esther Kim Lee, A History of Asian American Theatre, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Josephine Lee, ‘Stage Orientalism and Asian American Performance from the Nineteenth in the Twentieth Century’ in Rajini Srikanth & Min Hyoung Song, (eds.) The Cambridge History of Asian American Literature. Cambridge University Press; 2015

- Ralph Marsden ‘Melbourne’s Forgotten Movie Studio’ in On Stage, Vol 10, No 2, 2009 (Part 1) and Vol 10, No 3, 2009 (Part 2) Theatre Heritage Australia.

- Neville Meaney, Towards a New Vision, Australia and Japan across time, University of New South Wales Press, 2007

- Andrew Pike & Ross Cooper, Australian Film 1900-1977, Oxford University Press, 1980.

- Mark St Leon, Circus, The Australian Story, Melbourne Books, 2011.

- Angela Woollacott, Race and the Modern Exotic. Three ‘Australian’ women on Global Display. Monash University Publishing, 2011

Footnotes

| ↑1 | National Archives of Australia. SP42/1, C1931/3848, Henry Kakusaura Matsumoto |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 26 April 1913, p6 |

| ↑3 | Daily Herald (Adelaide) 27 November 1912, p9 |

| ↑4 | St Leon (2011) pps155-6 |

| ↑5 | He apparently adopted the first name ‘Henry’ on arrival in Australia |

| ↑6 | Killoran (2023) p153 |

| ↑7 | Sizeable in the north of Queensland, but Armstrong (1973) p8 estimates there were never more than 3,000 Japanese in the entire colony |

| ↑8 | See Neville Meaney (2007) p18-19 |

| ↑9 | Attorney-General Alfred Deakin, 12 September 1901 |

| ↑10 | See Esther Kim Lee (2006), p14. However, Elizabeth Craft suggests a Korean actor “Du Gle Kim” first played the role in the US. Craft (2024) p100 |

| ↑11 | Elizabeth Craft (2024) p236 |

| ↑12 | Josephine Lee (2015) p63 |

| ↑13 | The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio) 16 October, 1911, p14 |

| ↑14 | Elizabeth Craft (2024) p100 |

| ↑15 | Punch (Melbourne) 21 Nov 1912, p42 |

| ↑16 | The tour was extended three times; in December 1912, May 1913 and May 1914. The contracts survive in the Australian Performing Arts Collection |

| ↑17 | Marsden (2009) p4 |

| ↑18 | Pike & Cooper (1980) p80 |

| ↑19 | The Theatre Magazine (Sydney) 1 October 1915, p16 |

| ↑20 | National Archives of Australia. C1912/21405, Frank Seegoolam |

| ↑21 | National Library of Australia. J.C. Williamson scrapbooks of music and theatre programmes, Sydney and Melbourne, 1905-1921. PROMPT Scrapbook 8 – Vol 3, p129 |

| ↑22 | The Daily Telegraph (Sydney) 2 September 1916, p2 |

| ↑23 | Truth (Sydney) 14 October 1934, p21 |