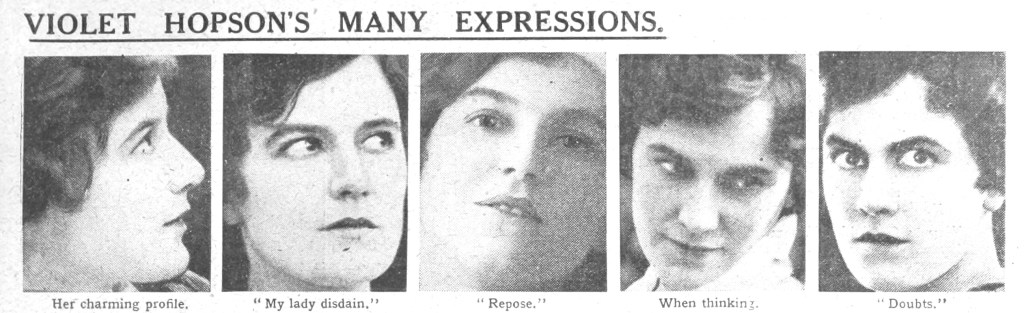

Above: Enlargement of Violet Hopson on an undated postcard – while working for Cecil Hepworth. Postcard in the author’s collection.

| The five second version. Born in Port Augusta, South Australia in 1887 as Elma Kate Victoria Karkeek,[1]Janice Healey, a British Film Institute librarian, is acknowledged with having first identified Violet Hopson’s real name. See Clare Watson (et al) Women and Silent British Cinema, however her … Continue reading Violet Hopson went on to a spectacular career in the British film industry in the 1910s and 20s. She has been widely recognised as one of the British cinema’s first female film stars, with an impressive 120 film appearances (mostly made between 1912 and 1925) to her credit. She worked with pioneer producer- director Cecil Hepworth and later in partnership with Walter West. In addition to her status as a popular British actor, she was also a producer on several successful films. She died in London in 1973, having obscured an Australian birth and childhood all her life. She was married to actor Alec Worcester from 1909-1918. Her sisters Zoe Karkeek (1879-1967) and Wilmot Karkeek (1880 -1962) were performers with Pollards Opera Company, Wilmot also appearing in India, South Africa and Britain with great success. |

In his 2005 book on the British film industry, Shepperton Bablyon, Matthew Sweet observes that many of Britain’s silent stars have left only fragments of their real, behind-the-screen stories for posterity. Thanks in part to “banal and mendacious publicity… their experiences have been turned and polished until they shine like lies.”[2]Matthew Sweet (2005) Shepperton Bablyon: The Lost Worlds of British Cinema. P35-36. Faber and Faber For up and coming actors, another factor was often in play too. Some had very human experiences they needed to disguise – embarrassing stories of disadvantage, divorce or illegitimacy. This also appears to have been the case for Violet Hopson, one of Britain’s first film stars.

A childhood in Australia… or California?

Throughout her life, Violet Hopson successfully maintained the pretence she was born in places other than Australia, most commonly claiming California. The Californian claim appeared repeatedly in film fan magazines and on official documents such as census returns, and this claim finally found its way into respected texts. We cannot know for certain why she went to such effort to do this, but clues exist in surviving records of her childhood, which suggest periods of turmoil and insecurity.

She was born Elma Kate Victoria Karkeek in 1887,[3]South Australia Geneology – Elma Kate Victoria Karkeck (sic), doc 409/139 in Port Augusta, South Australia, (but called Kate by the family) the youngest of four children born to William Charles Karkeek, a carpenter, and Josephine Lauretta nee Reynolds, a master mariner’s daughter from Hobart. Despite their fifteen year relationship, there is no record of a marriage between William and Josephine Lauretta.[4]A decade earler, in October 1867, sixteen year old Josephine had married miner John Henry Whitburn in the goldfields town of Maldon, Victoria. She bore him five children before the marriage failed … Continue reading Elma Kate Karkeek’s older siblings were Ora Zoe (usually just called Zoe, born 1879), Lauretta (sometimes spelled Lauratta, but usually known as Wilmot, born 1880) and Eugene Charles Byron (born 1886).[5]South Australia Geneology, docs 215/45, 252/174 and 369/226 respectively. By 1890 the family had moved to Adelaide – with Wilmot and Ora attending Sturt St Primary School, and their father William being described in the school register as a cabinet maker.[6]Sturt St Primary School. South Australia, School Admission Registers, 1873-1985. Via Familysearch.org Unfortunately, William died later the following year, probably leaving his family in a difficult state financially.[7]The Port Augusta Dispatch, Newcastle and Flinders Chronicle (SA) Fri 6 Nov 1891, P2, Family Notices, Via National Library of Australia’s Trove Sometime after this, Josephine Lauretta, now working as a dressmaker, moved to Sydney.

Josephine’s fortunes changed in January 1898, when she married Nicholas Hopson, a successful draper, property owner and prominent Sydney freemason. But prior to this, Josephine had also reinvented herself – she borrowed her older daughters’ names and now called herself Laura Zoe Karkeek, while claiming she had been born in Cannes, France![8]However Josephine Karkeek can still be identified by her accurately recorded parent names. See New South Wales Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Marriage certificate Nicholas Hopson & … Continue reading If Josephine wanted to impress her new husband with stories of an exotic upbringing it was a wasted effort – less than six months later, Hopson succumbed to pneumonia.[9]The Daily Telegraph (Syd), Thu 23 Jun 1898, P5, PERSONAL, Via National Library of Australia’s Trove

On Hopson’s death, Josephine (and Hopson’s son by a previous marriage) inherited an estate worth £14,600. The estate was mostly in Sydney rental properties, which must have assured her of a steady income and provided some welcome security for the family.[10]NSW State Archives. Nicholas Hopson, Probate, Date of Death 22 June 1898, Lewisham NSW. NRS-13660-4-654-Series 4_15968

At about the same time, both Zoe and Wilmot pursued careers on stage. By 1892, they were regulars in Tom Pollard’s branch of the Pollards Lilliputian Opera Company – they both performed using the surname Karkeek.[11]See The Express and Telegraph (SA) Sat 22 May 1897, P1, Advertising, Via National Library of Australia’s Trove. There is no evidence that Kate Karkeek joined her sisters performing with the Pollards, although it is often claimed she did. There is a single reference to a young Kate Karkeek performing twice in an amateur opera company in Christchurch, New Zealand, but no more.[12]See Otago Witness (NZ), 8 March 1900, P50. Theatrical and Musical Notes by Pasquin. Via National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past This seems to be because in early 1900, shipping records show Zoe departed New Zealand and took her sister Kate to the UK, via New York, to join her mother, who had apparently already left.[13]Zoe and Kate arrived in England from New York on the SS Manitou, on 1 August 1900. Newspaper reports and a US census entry for 1900 suggest they spent some time in New York

On becoming a villainess, and “England’s leading cinema star…”

Violet Hopson’s own brief statements on her childhood also reflect a determination to continue to construct an image of a comfortable middle class upbringing.[14]A 1901 UK census entry exists, listing Violet and her mother visiting music teacher and composer George Eyton in Douglas, the capital of the Isle of Man. The document notes Elma Kate Victoria Hopson, … Continue reading She later claimed that “she was brought to England by her parents when quite small and… educated in a French Convent.”[15]Motion Picture Studio, 3 December 1921. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library She appeared in the chorus of George Edwardes’ The Merry Widow at Daly’s Theatre and was noted in newspapers in May 1909, when the musical toured through English cities.[16]Rugby Advertiser, 29 May 1909. Via British Library Newspaper Archive Unfortunately, there is almost no other reliable information surviving to confirm where she lived or studied in England before 1909. Exactly when she adopted the stage name Violet Hopson we do not know. However, a very real influence on her in the first years of the new century must have been the success being enjoyed by her sister Wilmot, who was performing around the world with the Maurice Bandmann company.(See below).

With her in the George Edwardes troupe was Alec Worcester (real name – Alexander Worster) , whom she would marry in June 1909, while in Luton. The marriage certificate listed Violet’s father as “Clarence Hopson,” a gentleman. Again, this was a creative interpretation of events apparently designed to obscure her more mundane childhood. Over the next few years, two children were born of the marriage – Nicholas and Jessica.

The autobiography of Cecil Hepworth, the pioneer English producer-director who first employed Violet (and Alec Worcester) has little to tell us about her involvement or her entree to the film industry. She was “a good actress and a very nice woman” was about all he could write in 1951 – although he was less impressed with Worcester as a person and actor. The Umbrella They Could Not Lose (1912) has been identified as Violet’s first confirmed film for Hepworth.[17]Denis Gifford (1986) The British Film Catalogue 1895-1985, a reference guide: 151, David & Charles. It has been suggested that she performed in Mr Tubby’s Triumph, made by Cricks and Martin … Continue reading

Unfortunately, almost all of Hepworth’s early films are lost – the negatives sold for their silver value in later years. A few exceptions survive, including I do like to be where the girls are (1912), which features Violet as a member of the chorus of dancers and then suffragettes. The accompanying song was performed by comedian Jack Charman, to be played in synch with the film, an example of a technique that Hepworth developed known as Vivaphone. (Watch it here)

Promoted by Hepworth as “the dear delightful villainess” one film fan magazine reported that “Violet had that clever knack of making you like… and dislike her… at the same time.”[18]The Picture Show, 26 June 1919; 17. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library But Violet’s villainess was also a more complex woman for the new century. In 1919, Violet herself observed “I find my screen characters are popular because I usually portray women who are strong willed… The fluffy irresponsible type of woman may be popular… but I think our returned warriors are looking for the reliable, capable girls as mothers of the coming generation.”[19]The Picture Show, 17 May 1919, P9. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library

Also surviving of her many early films is one of the comedies she appeared in for Hepworth in 1916 – Tubby’s Typewriter (Watch it here – minus the final scene). Here, Tubby and his new wife have a marital spat over a misunderstanding about a typewriter (taken to mean typist by Violet’s character Mrs Tubby). How different this mildly amusing but rather restrained “comedy of manners” is when compared to the comedy shorts being produced at the same time in the US.

After an extremely busy five years with Hepworth, appearing in both his shorts and sometimes in his experiments with longer narratives, Violet Hopson left to join Walter West at Broadwest films, her first film being The Ware Case (1917), based on the popular stage play. She had also separated from Worcester in 1916, a divorce was granted in late 1918.[20]Worster v Worster, UK Divorce Court file J77/1396/2853. Of note, the divorce documents are marked not for release until 2020. Via Ancestry.com

Violet quickly became the leading actress of choice at Broadwest, and some newspapers even reported she was married to Walter West. But although they enjoyed a successful professional and apparently also personal relationship – there is no evidence that the couple were married. [21]Also -in Electoral registers and census returns she was still named Elma Kate Worster. And on her death certificate she was still Elma Kate Worster However, it was while working with West that her career blossomed and she became – in the opinion of film historian Rachael Low – “the first British actress to be exploited as glamorous and well dressed… despite a personality which made little real impact from the screen.”[22]Rachael Low (1948) The History of the British Film, 1918-1929 : 263. George Allen and Unwin

As Christine Gledhill has pointed out, contemporary publicity surrounding Hopson’s career tended to emphasize that her success had been “won by her own unaided efforts and hard work.”[23]Christine Gledhill (2007) “Reframing Women in 1920s British Cinema: the case of Violet Hopson and Dinah Shurey.” Journal of British Cinema and TV, Vol 17, No 3, 2007. Edinburgh University … Continue reading While this was a “familiar trope of stardom”, Hopson had good reason to be conscious of how hard she had worked and how far she had come.

In 1919 Violet Hopson produced her first film – about horse racing – one of her own interests, called A Gentleman Rider or Hearts and Saddles. This was directed by West, starring Violet and her regular co-star Stewart Rome. She produced several more successful films on horse racing themes – Kissing Cup’s Race (1920) and The Scarlet Lady (1922), while also appearing in other Broadwest films. These turf dramas found an audience – in the words of one fan who wrote to Hopson; “I prefer girls who can stick up for themselves and your characters are just right…Lady Lancelot in…[A Fortune at Stake] – she was my ideal woman. A thorough sportswoman, yet so sympathetic”[24]The Picture Show, 17 May 1919, P9. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library

Needless to say, not all of her films for Broadwest were enthusiastically received. For example, reviewing the drama Her Son in June 1920, The Bioscope felt both Stewart Rome and Violet Hopson were too restrained and their portrayals superficial.[25]The Bioscope 17 June 1920. British Library Newspaper Archive Yet, Violet’s successes at Broadwest were regular enough to inspire her to provide public commentaries on the art of acting – and the problems of finding young people willing to make the effort to be good screen actors. “Few are willing to undergo the drudgery necessary for them to learn the business” she told Variety in June 1921. ” I know from experience there is no easy road to success in film acting.“[26]Variety, 17 June 1921, Vol 63, Issue 4, P36. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library

Financial troubles and the end of career…

Unfortunately, Broadwest ran into financial difficulties in 1924. In 1921, West and Hopson had entered into a widely reported contract with Butcher’s Film Service to make 12 films, and in return a large investment was made.[27]Leeds Mercury, 10 December 1921, P5. Also see The Bioscope, 3 January 1924, P68-9, where Butcher’s outline their upcoming releases. Via British Library Newspaper Archive They managed to make ten films, but Stirrup Cup Sensation was still incomplete when Walter West was declared bankrupt late in the second half of 1924.[28]Variety 17 September 1924, via Lantern, Media History Digital Library Butcher’s had to find another £400 to complete it and claimed damages for the delay – pursuing Violet particularly, as West was already bankrupt.[29]Kinematograph Weekly 18 March 1926, P46. Via British Library Newspaper Archive It seems this financial crisis brought Violet’s personal and professional partnership with West to an end – there were no more films together. By 1929 she could tell The Era that she had “severed all business association with Walter West.”[30] The Era, 10 July 1929, P6. Via British Library Newspaper Archive

However, Violet did not abandon her interest in acting. She performed in two more films of note – Remembrance (1927) sponsored by the British Legion, and the film Widecombe Fair (1928), released just before the advent of sound. Now aged in her early forties, she busied herself experimenting with a drama school for screen actors, and also tried her luck as a costume designer for the theatre.[31]The Bioscope, 27 January 1927, P27, Via British Library Newspaper Archive In 1929 she joined a tour of the play Interference, before becoming “Hostess” at The Commodore, a palatial newly-built cinema just outside London, where she sometimes gave talks on screen beauty. [32]West London Observer, 10 January 1930, P4. Via British Library Newspaper Archive One can only admire her persistence in what were difficult personal circumstances, and the middle of the Depression.

Like many silent screen actors who lost their currency with the advent of sound films, Violet Hopson still continued to appear as an uncredited extra for some years – her last probably being as an extra in Storm in a Teacup in 1936.[33]Motion Picture Herald, Nov-Dec 1936. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library Meanwhile, newspapers would occasionally rhetorically ask and then reveal where she was. Even F Maurice Speed could assure readers of his 1971-2 Film Annual that she was alive and living happily in Essex. Unfortunately, she remained unwilling to speak publicly about her career to anyone. Reluctantly responding to a request for an interview in 1947, this once leading figure in the British film industry said “It is all so long ago… I am (now) leading an entirely private, happy, life” [34]Evening Standard, London, 4 July 1947, P4. via Newspapers.com – in other words, Violet had nothing to say.

Violet Hopson died in Kensington, London, 21 July 1973. She was survived by her two children from her marriage to Alec Worcester. Her maiden name and Australian birth were confirmed in her death certificate.

Wilmot and Zoe’s Careers

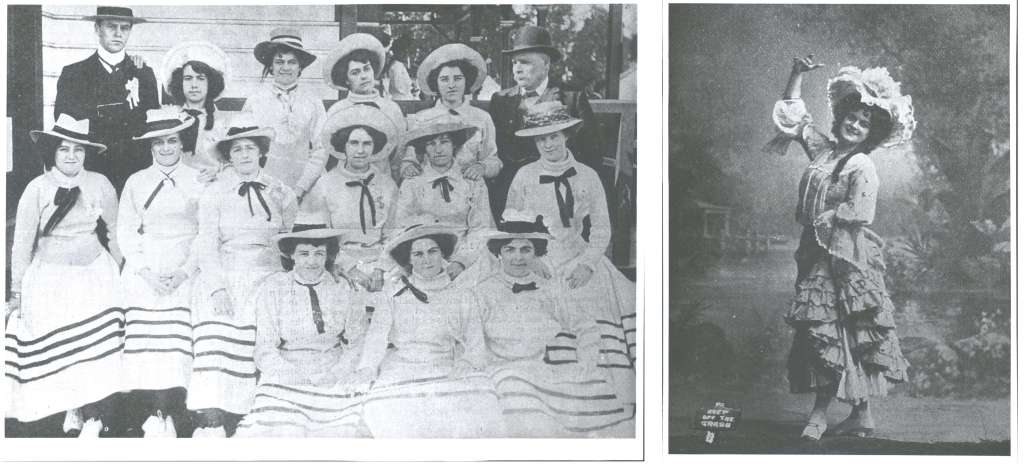

Between 1892 and 1902 Wilmot and Zoe were active with Tom Pollard’s branch of Pollard’s Liliputian Opera Company, which toured Australasia with a repertoire of popular musical comedies – The Geisha, Floradora, The Toreador and the like. Also in the company were other performers who would make a name for themselves – including Maud and May Beatty, and Alice Pollard.

Melbourne, 1892. Via State Library of Victoria

As noted, Zoe Karkeek left the Pollard company in February 1900, and escorted Kate to the UK via the United States.[35]Taranaki Herald 14 Feb 1900, P2 via National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past. Writing to New Zealand friends from New York some months later, Zoe explained she was “resting” between engagements. She arrived in England with Kate in August 1900 but returned alone and rejoined Pollards Opera Company in Melbourne in March 1901.[36]Otago Witness, 6 March 1901, P54 via National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past In December 1903, while on a Pollard’s tour of South Africa, (operating under the title of Royal Australian Opera Company) Zoe married Stacey William Beaufort Grimaldi, a detective in the Natal Police, and soon after she retired from the stage for good.[37]The Mercury (Tas.) 13 February 1904, P11, DRAMATIC NOTES.

About the same time, Wilmot began a long association with the Maurice Bandmann (1872-1922) Opera Company. Bandmann was a theatre entrepreneur who ran performance troupes throughout the English-speaking “settler colonies”. While the recent history of Bandmann and his company doesn’t mention Wilmot by name,[38]Christopher Balme (2020) The Globalization of Theatre 1870-1930: The Theatrical Networks of Maurice E. Bandmann. Cambridge University Press. newspaper reports and shipping manifests show her continually on the move to perform on Bandmann’s circuit – regularly appearing in India, South America, Hong Kong and Japan between 1904 and 1912. Between fulfilling contracts for Bandmann, Wilmot also appeared on stage in England, most notably in 1912-1916.

Wilmot Karkeek arrived in South Africa again in December 1921, as part of another performing troupe. What her subsequent history was, is currently unknown. However, in June 1962, an 81 year old Australian born woman called Lauretta Karkeek died at the Ingutsheni Hospital for the mentally ill in Bulawayo, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe). Other than her distinctive name, age and country of birth, nothing else was recorded about her for the death certificate. It seems very likely that this was Wilmot.[39] Death Notice Lauretta Karkeek, Ingutsheni Hospital, 25 June, 1962. Zimbabwe Death Registers, Death Register, 1892-1977. Via familysearch.org

Zoe Grimaldi spent some of her later life with her husband in South Africa but died in Wandsworth, England, where they had retired, in 1967. Zoe returned to Australia on a visit in 1923, possibly the only member of the family to do so.

Violet’s brother, Eugene Charles Byron Karkeek, may have joined the Australian Army in World War I. Violet made several references to her brother being “with the Australians” – and one account of his being with a party burying the dead during the May 1915 Gallipoli truce seems particularly personal and plausible. [40]The Picture Show, 24 May 1919: 24. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library However, there is no person with that name listed in the very comprehensive Australian military records for World War I. If he enlisted, it was under another name, and at the time of writing, searches have not revealed him.

Nick Murphy

January 2022

References

Text

- Christopher Balme (2020) The Globalization of Theatre 1870-1930: The Theatrical Networks of Maurice E. Bandmann. Cambridge University Press.

- Melody Bridges & Cheryl Robson (Eds) (2016) Silent Women: Pioneers of Cinema. Supernova Books.

- Peter Downes (2002) The Pollards. A Family and its child and adult opera companies in NEw Zealand and Australia 1880-1910. Steele Roberts.

- Denis Gifford (1986) The British Film Catalogue 1895-1985, a reference guide: 151, David & Charles.

- Christine Gledhill (2007) “Reframing Women in 1920s British Cinema: the case of Violet Hopson and Dinah Shurey.” Journal of British Cinema and TV, Vol 17, No 3, 2007. Edinburgh University Press

- Cecil M Hepworth (1951) Came the Dawn – Memories of a film Pioneer. Phoenix House.

- Rachael Low (1948) The History of the British Film, 1918-1929. George Allen and Unwin

- Brian McFarlane (2003) The Encyclopedia of British Film. Methuen BFI

- Matthew Sweet (2005) Shepperton Bablyon: The Lost Worlds of British Cinema. Faber and Faber

Online

- Oxford Dictionary of Biography. Frank Gray (2021) Hepworth, Cecil Milton (1874-1953)

- Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Peter Downes (1993) ‘Beatty, May’.

- Clare Watson (et al) Women and Silent British Cinema

Film

- I do like to be where the girls are (1912) “Films by the Year” on Youtube. An unusual example of a recorded song that was synched to film.

- Tubby’s Typewriter (1916) BFI channel on Youtube. The only one of the very popular Tubby shorts available today.

- Heppy’s Daughter – an Interview with Cecil Hepworth’s daughter on Youtube. Kennington Bioscope

- The Vintage Negatives site on Youtube has recreated some of Cecil Hepworth’s lost films, including several with Violet Hopson, using high quality stills.

Newspaper & Magazine Sources

- National Library of Australia’s Trove

- National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past

- Newspapers.com

- British Library Newspaper Archive

- Lantern, the Media History Digital Library

Primary Sources

- Familysearch.com

- Ancestry.com

- South Australian Geneology

- New South Wales State Archives

- Victoria, Births, Deaths and Marriages

- New South Wales, Births, Deaths and Marriages

- General Register Office, HM Passport Office.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Janice Healey, a British Film Institute librarian, is acknowledged with having first identified Violet Hopson’s real name. See Clare Watson (et al) Women and Silent British Cinema, however her identity is also confirmed in her Australian birth and British death certificates |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Matthew Sweet (2005) Shepperton Bablyon: The Lost Worlds of British Cinema. P35-36. Faber and Faber |

| ↑3 | South Australia Geneology – Elma Kate Victoria Karkeck (sic), doc 409/139 |

| ↑4 | A decade earler, in October 1867, sixteen year old Josephine had married miner John Henry Whitburn in the goldfields town of Maldon, Victoria. She bore him five children before the marriage failed sometime in the late 1870s, although there is no record the couple formally divorced. See Mount Alexander Mail (Vic) Thu 31 Oct 1867, P2, Family Notices, Via National Library of Australia’s Trove. Also see Victoria, Births Deaths and Marriages, Document 3721/1867 Marriage of John Henry Whitburn and Josephine Reynolds. |

| ↑5 | South Australia Geneology, docs 215/45, 252/174 and 369/226 respectively. |

| ↑6 | Sturt St Primary School. South Australia, School Admission Registers, 1873-1985. Via Familysearch.org |

| ↑7 | The Port Augusta Dispatch, Newcastle and Flinders Chronicle (SA) Fri 6 Nov 1891, P2, Family Notices, Via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑8 | However Josephine Karkeek can still be identified by her accurately recorded parent names. See New South Wales Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Marriage certificate Nicholas Hopson & Laura Zoe Karkeek,1702/1898 |

| ↑9 | The Daily Telegraph (Syd), Thu 23 Jun 1898, P5, PERSONAL, Via National Library of Australia’s Trove |

| ↑10 | NSW State Archives. Nicholas Hopson, Probate, Date of Death 22 June 1898, Lewisham NSW. NRS-13660-4-654-Series 4_15968 |

| ↑11 | See The Express and Telegraph (SA) Sat 22 May 1897, P1, Advertising, Via National Library of Australia’s Trove. |

| ↑12 | See Otago Witness (NZ), 8 March 1900, P50. Theatrical and Musical Notes by Pasquin. Via National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past |

| ↑13 | Zoe and Kate arrived in England from New York on the SS Manitou, on 1 August 1900. Newspaper reports and a US census entry for 1900 suggest they spent some time in New York |

| ↑14 | A 1901 UK census entry exists, listing Violet and her mother visiting music teacher and composer George Eyton in Douglas, the capital of the Isle of Man. The document notes Elma Kate Victoria Hopson, as a 14 year old “born in Wales” while Josephine is again “Lauratta Zoe Hopson” and “born in France.” Via Ancestry.com |

| ↑15 | Motion Picture Studio, 3 December 1921. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library |

| ↑16 | Rugby Advertiser, 29 May 1909. Via British Library Newspaper Archive |

| ↑17 | Denis Gifford (1986) The British Film Catalogue 1895-1985, a reference guide: 151, David & Charles. It has been suggested that she performed in Mr Tubby’s Triumph, made by Cricks and Martin in 1910, but records and credits for this film are sparse and the film no longer exists. |

| ↑18 | The Picture Show, 26 June 1919; 17. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library |

| ↑19, ↑24 | The Picture Show, 17 May 1919, P9. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library |

| ↑20 | Worster v Worster, UK Divorce Court file J77/1396/2853. Of note, the divorce documents are marked not for release until 2020. Via Ancestry.com |

| ↑21 | Also -in Electoral registers and census returns she was still named Elma Kate Worster. And on her death certificate she was still Elma Kate Worster |

| ↑22 | Rachael Low (1948) The History of the British Film, 1918-1929 : 263. George Allen and Unwin |

| ↑23 | Christine Gledhill (2007) “Reframing Women in 1920s British Cinema: the case of Violet Hopson and Dinah Shurey.” Journal of British Cinema and TV, Vol 17, No 3, 2007. Edinburgh University Press |

| ↑25 | The Bioscope 17 June 1920. British Library Newspaper Archive |

| ↑26 | Variety, 17 June 1921, Vol 63, Issue 4, P36. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library |

| ↑27 | Leeds Mercury, 10 December 1921, P5. Also see The Bioscope, 3 January 1924, P68-9, where Butcher’s outline their upcoming releases. Via British Library Newspaper Archive |

| ↑28 | Variety 17 September 1924, via Lantern, Media History Digital Library |

| ↑29 | Kinematograph Weekly 18 March 1926, P46. Via British Library Newspaper Archive |

| ↑30 | The Era, 10 July 1929, P6. Via British Library Newspaper Archive |

| ↑31 | The Bioscope, 27 January 1927, P27, Via British Library Newspaper Archive |

| ↑32 | West London Observer, 10 January 1930, P4. Via British Library Newspaper Archive |

| ↑33 | Motion Picture Herald, Nov-Dec 1936. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library |

| ↑34 | Evening Standard, London, 4 July 1947, P4. via Newspapers.com |

| ↑35 | Taranaki Herald 14 Feb 1900, P2 via National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past |

| ↑36 | Otago Witness, 6 March 1901, P54 via National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past |

| ↑37 | The Mercury (Tas.) 13 February 1904, P11, DRAMATIC NOTES. |

| ↑38 | Christopher Balme (2020) The Globalization of Theatre 1870-1930: The Theatrical Networks of Maurice E. Bandmann. Cambridge University Press. |

| ↑39 | Death Notice Lauretta Karkeek, Ingutsheni Hospital, 25 June, 1962. Zimbabwe Death Registers, Death Register, 1892-1977. Via familysearch.org |

| ↑40 | The Picture Show, 24 May 1919: 24. Via Lantern, Media History Digital Library |